Indigo was on the last 400 miles on the U.S. walk and on the last part of the European walk through Greece. She is Water's sister in Pittsburgh. In giving us a tour of their home, we were enthralled by a family of beavers who had made their home along the Allegheny River not far from downtown, a sign that water quality had improved. The air quality had also significantly improved in the past 20-30 years. Pittsburgh is now a leader in green building. During a quiet moment, I had a chance to talk with Indigo about the walks and her life.

“The U.S. walk was a major marker in my life," she said. "It came at a time when my whole life changed in 1984. By the time I made the decision to go on the walk at the end of September, my sister had died and my marriage had ended, so it was perfect timing. It was an empowerment exercise for me. I could walk by my own steam any place. I needed to change, to move, and the fact that I could walk 400 miles was empowering me, putting wind in my sails. Every day that I walked strengthened that. I had been familiarized with community through my visit to Findhorn in 1982, and I had been involved in a sweat lodge circle in Philadelphia, so all those components had me ready for the walk. It was an easy transition—I had a brother on the walk and the walk was pretty together by then. The walkers were all individuals, but they challenged themselves to work together.”

Highlights for Indigo after the walk included traveling to the Soviet Union with a group of artists in 1990 as part of a vision by Raisa Gorbachev and finding a flyer on the street in South Philly that advertised a sacred dancing event before the Great Pyramid in Egypt. “The dance opened a gateway that will remain open until 2011,” she said. “Eleven dances are supposed to occur by then and eight have been done so far. Each one has a certain tone associated with them. Had 130 people from 35 countries participate in the last dance. It’s been my spiritual driver. In the meantime, there were missions like with Water’s spiritual teacher. His mission was to have this peace dance. He saw what I was doing. Did a dance in 1993 and had people native to Ecuador come to do a dance. Purpose—opens a gateway to consciousness either evolutionary or to lay in certain energies. Each gate has a certain tone and energy. What attracts me is its movement with people from all over the world and we come together and work together and it seems like things change. If we love and trust one another, things get better. This group makes this be a focus. It’s not like it’s a religion or a movement, more a way of being.” For more information on the dances, log onto www.nvisible.com.

For her day job, Indigo works as an environmental educator focusing on responsible energy use in homes and businesses. She creates and implements education programs for grades 4 through 12.

To end the East Coast tour, we had a wonderful event at the Quest Bookshop in Charlottesville, Virginia. Our hosts were my adopted sister Ana Aegis (formerly Ann Clothiaux) and her partner Paul. Ana had participated in our 3-week walk in the Pacific Northwest in the late 1990s. It was great to see them and to roam around this progressive and attractive small city in the shadow of the Shenandoahs.

Thursday, July 5, 2007

Wednesday, July 4, 2007

Water Saudauskas: "The hardest step is out the front door"

In Pittsburgh, we stayed with former walkers Water Saudauskas and Indigo Raffel and held three gatherings with diverse and warm people. In the first gathering, one sweat leader named Johnny sang a sweat song for the group. I later spoke with Water about the walk and what he’s been doing since. “Highlights for me on the walk was gaining the ability after about a month to walk 18 miles and knowing that it was doable and easy, enabling me to become a migratory spiritual animal. Walking enabled me to enter the room of earth balancing where prior I was just knocking at the door, so that I could touch without any repercussions a wild rattlesnake. People we met thought we were doing things that they thought were impossible to them, but in talking with them they realized they could do it—it just takes practice. It is step by step, inch by inch. The hardest step is out the front door.”

Early in the morning during our stay, before dawn, Water left his house to visit a nearby park to “walk into the mystery of the forest.” Water added, “I don’t think I would have that gift without the walk. People use the word balance, to walk in balance, usually in books. I know in my guts and in the soles of my feet what that means because of the walk. I know that I can access it when I do walk.”

What are the highlights of Water’s life since the walk? “I held my father when he was dying so I received a vision that I hope I can manifest in my lifetime; sweating and working to humble myself for ten years with a Mexican-American Buddha-like Vietnam Vet named Luciano Perez; working with my emotionally devastated brother for the last 22 years in Pittsburgh. He’s a lot better because of that. Living in a transitional interracial neighborhood where walking and praying is a survival technique, not something that has an exercise value. It’s a way of living here to survive. In 2000, a mentally-ill African American man went on a killing spree, consciously killing three non-African American people and wounding two. To heal the torn interracial neighborhood, the churches two weeks later had a peace walk that drew 500 people to start to heal the wounds from this man on the community.

“On October 25th, 2001, I stood on Broadway looking into the smoldering hole of 911 praying with seven others that healing would go on. Through the walk and the spiritual discipline of Luciano Perez I had a sense of wonder and respect. The walk started me in arriving there, 17 years later.

“I’m almost 59 now. I don’t have a car, so I use my legs and ride buses. Walking helps me keep sane; that’s correlated to the walk. The walking grounds me so that I don’t put out the fear vibrations to the animals.”

Early in the morning during our stay, before dawn, Water left his house to visit a nearby park to “walk into the mystery of the forest.” Water added, “I don’t think I would have that gift without the walk. People use the word balance, to walk in balance, usually in books. I know in my guts and in the soles of my feet what that means because of the walk. I know that I can access it when I do walk.”

What are the highlights of Water’s life since the walk? “I held my father when he was dying so I received a vision that I hope I can manifest in my lifetime; sweating and working to humble myself for ten years with a Mexican-American Buddha-like Vietnam Vet named Luciano Perez; working with my emotionally devastated brother for the last 22 years in Pittsburgh. He’s a lot better because of that. Living in a transitional interracial neighborhood where walking and praying is a survival technique, not something that has an exercise value. It’s a way of living here to survive. In 2000, a mentally-ill African American man went on a killing spree, consciously killing three non-African American people and wounding two. To heal the torn interracial neighborhood, the churches two weeks later had a peace walk that drew 500 people to start to heal the wounds from this man on the community.

“On October 25th, 2001, I stood on Broadway looking into the smoldering hole of 911 praying with seven others that healing would go on. Through the walk and the spiritual discipline of Luciano Perez I had a sense of wonder and respect. The walk started me in arriving there, 17 years later.

“I’m almost 59 now. I don’t have a car, so I use my legs and ride buses. Walking helps me keep sane; that’s correlated to the walk. The walking grounds me so that I don’t put out the fear vibrations to the animals.”

Tuesday, July 3, 2007

Suzanne Carlson: Beating Swords into Plowshares

Cyndi and I drove to Greenfield, Massachusetts to meet with walk veteran Suzanne Carlson and four members of the Kumik intertribal Native American group. We exchanged sacred tobacco and other gifts and had an inspirational discussion for about three hours. Nearby was an historic village site, now on an island in a reservoir, that they said was a sacred place of peace where people of many tribes could meet in safety for trade and rest. Colonists massacred the village inhabitants in the 1600s and the Kumik group does healing ceremonies on the anniversary of the massacre. Their leader is a clear-eyed woman named Strong Oak.

I also interviewed Suzanne, who was on the cross-continental walk. Walk highlights for her included being able to come together in community, gorgeous scenery, climbing into the Sierra mountains, hot springs, connecting with a peace pilgrimage of Europeans, the gathering with the Kaibab Paiutes, Wounded Knee, meeting Glenda Banks and several Native American runners returning from the Jim Thorpe Run, West Virginia’s cranberry bogs, and many other places and events. “The walk gave me a closer connection to the earth,” she said, “and a sense of how out of balance this culture is. We have to learn the wisdom of the elders, especially in valuing the commons and the community above one’s egocentric needs and desires.”

Through a connection with a man named Leo, who was on the walk for the first couple of days, Suzanne learned about the plowshares actions against the nuclear war machine. The group’s name is derived from the biblical concept of beating swords into plowshares. Suzanne eventually participated in a plowshares action, one that involved hammering on a trident missile tube and pouring blood on it. As a result, she served 11 months in prison in Alderson, West Virginia. “I had lots of support while in prison,” she says. “That was my statement of saying no to weapons and yes to life.”

Since the walk, Suzanne has also worked at a homeless shelter and on an organic farm. She currently works at a food coop in Greenfield and is still active in many causes, especially in promoting sustainability on a local level.

I also interviewed Suzanne, who was on the cross-continental walk. Walk highlights for her included being able to come together in community, gorgeous scenery, climbing into the Sierra mountains, hot springs, connecting with a peace pilgrimage of Europeans, the gathering with the Kaibab Paiutes, Wounded Knee, meeting Glenda Banks and several Native American runners returning from the Jim Thorpe Run, West Virginia’s cranberry bogs, and many other places and events. “The walk gave me a closer connection to the earth,” she said, “and a sense of how out of balance this culture is. We have to learn the wisdom of the elders, especially in valuing the commons and the community above one’s egocentric needs and desires.”

Through a connection with a man named Leo, who was on the walk for the first couple of days, Suzanne learned about the plowshares actions against the nuclear war machine. The group’s name is derived from the biblical concept of beating swords into plowshares. Suzanne eventually participated in a plowshares action, one that involved hammering on a trident missile tube and pouring blood on it. As a result, she served 11 months in prison in Alderson, West Virginia. “I had lots of support while in prison,” she says. “That was my statement of saying no to weapons and yes to life.”

Since the walk, Suzanne has also worked at a homeless shelter and on an organic farm. She currently works at a food coop in Greenfield and is still active in many causes, especially in promoting sustainability on a local level.

Wednesday, June 27, 2007

Robin Rieske--"We have to keep these stories alive"

Robin was on the United States walk and helped beforehand with mailouts. She was 20 years old during the walk and a college student at Florida State. She currently lives in Brattleboro, VT and works as a certified substance abuse prevention consultant, community organizer and a media literacy educator. She is still active politically, especially around the impact of media on public health and democracy. She is married to Breeze and she has a stepson named Silas who is heading off to college. Her main passion is belly dancing. "I was a sociology student at the time of the walk. Being on the walk gave me a real life experience in sociology and community. I had the book knowledge but I hadn't lived in a community before so I had a lot of lessons to learn and I still apply some of those lessons today. One of my biggest impacts from the walk is that I gained a huge appreciation for the natural beauty in this part of North America."

"There is so much to say about the walk.... the personal relationships, the day to day logistics of travelling, camping out, cooking, bathing, conflicts, healing, singing. There were powerful experiences of being with the native people and how these different cultures did exist and do exist. I think most of us grow up thinking that one way was the norm and it isn't. Working now with the government, I feel we are more aware of how the services we provide need to be geared toward the culture of those receiving the services whether it's low income families, racial diversity or gender differences. It's all a part of cultural competency. Because of the walk experience, I can now apply that a bit more.

"I've had no desire to go to high school and college reunions, but going to the walk reunions has helped me to keep alive the experience, the stories, the successes, the challenges and the beauty of community. Because we live in a media-saturated society we have to keep these stories alive, we need to tell stories that preserve our planet and not just the stories that our media culture attempts to sell us. Understanding this has helped me to understand the importance of story telling in all cultures and how we have to use our privilege to help others maintain their ability to speak! Dougs book, his tour, the reunions, these have been such great gifts. May we all cross paths again!"

"There is so much to say about the walk.... the personal relationships, the day to day logistics of travelling, camping out, cooking, bathing, conflicts, healing, singing. There were powerful experiences of being with the native people and how these different cultures did exist and do exist. I think most of us grow up thinking that one way was the norm and it isn't. Working now with the government, I feel we are more aware of how the services we provide need to be geared toward the culture of those receiving the services whether it's low income families, racial diversity or gender differences. It's all a part of cultural competency. Because of the walk experience, I can now apply that a bit more.

"I've had no desire to go to high school and college reunions, but going to the walk reunions has helped me to keep alive the experience, the stories, the successes, the challenges and the beauty of community. Because we live in a media-saturated society we have to keep these stories alive, we need to tell stories that preserve our planet and not just the stories that our media culture attempts to sell us. Understanding this has helped me to understand the importance of story telling in all cultures and how we have to use our privilege to help others maintain their ability to speak! Dougs book, his tour, the reunions, these have been such great gifts. May we all cross paths again!"

Mindi Bender--"I still feel the walk"

We had a wonderful program in Brattleboro last night, the gathering organized by walk veteran Robin Rieske. More than 50 people showed up. Robin had publicized the event in the local newspapers and Janisse Ray, an old friend and noted writer, wrote a good review of the book for the main newspaper. I enjoyed meeting many warm people including Woody, a Lakota/Dakota Native American. He knew some of the Native Americans depicted in my powerpoint such as Shorty, our guide through the Pine Ridge Reservation. I enjoyed all the hugs afterwards.

This morning, I talked with Mindi Bender, veteran of the U.S. and European walks and long time friend. She currently lives in Ann Arbor, Michigan, and works as a teacher of high school students with special needs. "I recall the great amount of diversity of the people on our walk, the people we met and the vastness of our country's land--the diversity of natural landscape. I wish that I could go back and experience it with my current perspective of being more present, with all the different individuals in different situations, being more involved at a deeper level. All of the phenomenal things we went through were part of our daily lives and I took it for granted that walking was just another way of life. Now I realize how phenomenal our journey was. I learned to be able to accept all kinds of different opinions and be more tolerant.

I loved being immersed in the sacredness of nature all of the time. I continue to seek nature to rejuvenate myself in times of stress and peace.

"Sometimes when I'm walking on paths of nature, I still have the perspective of looking for places to sleep or camp, like when I was on the walk. It's just a natural part of my mind now. With gratitude I honor the four directions when entering and leaving a space in nature. When I walk I still feel the energy coming from my chi center; I still have a fast walking gait, remembering walking 20 miles a day. Even when I walk down the corridors of my high school I think of the rivers and roads and various landscapes that we traversed. I still feel the walk in my body even when I walk through a hallway. I imagine walking the long distances from mountain to mountain. When I'm in a large city I try to seek out the natural spots. When I look at the stars I am reminded of the brightness of the stars in Nevada. The friendships I've made with the core group of walkers have continued and have been maintained through visits and reunions. They are so precious to me. These are the people with whom I love to hike, camp, and travel with in natural areas."

This morning, I talked with Mindi Bender, veteran of the U.S. and European walks and long time friend. She currently lives in Ann Arbor, Michigan, and works as a teacher of high school students with special needs. "I recall the great amount of diversity of the people on our walk, the people we met and the vastness of our country's land--the diversity of natural landscape. I wish that I could go back and experience it with my current perspective of being more present, with all the different individuals in different situations, being more involved at a deeper level. All of the phenomenal things we went through were part of our daily lives and I took it for granted that walking was just another way of life. Now I realize how phenomenal our journey was. I learned to be able to accept all kinds of different opinions and be more tolerant.

I loved being immersed in the sacredness of nature all of the time. I continue to seek nature to rejuvenate myself in times of stress and peace.

"Sometimes when I'm walking on paths of nature, I still have the perspective of looking for places to sleep or camp, like when I was on the walk. It's just a natural part of my mind now. With gratitude I honor the four directions when entering and leaving a space in nature. When I walk I still feel the energy coming from my chi center; I still have a fast walking gait, remembering walking 20 miles a day. Even when I walk down the corridors of my high school I think of the rivers and roads and various landscapes that we traversed. I still feel the walk in my body even when I walk through a hallway. I imagine walking the long distances from mountain to mountain. When I'm in a large city I try to seek out the natural spots. When I look at the stars I am reminded of the brightness of the stars in Nevada. The friendships I've made with the core group of walkers have continued and have been maintained through visits and reunions. They are so precious to me. These are the people with whom I love to hike, camp, and travel with in natural areas."

Tuesday, June 26, 2007

Massacusetts/Vermont events and walkers--Eric Herminghausen

Cyndi and I drove to Greenfield, Massachusetts, where we gave a program at a community non-denominational church. It was organized by Suzanne Carlson, veteran of the United States walk and an ardent peace activist for most of her adult life. We had a warm sharing. The minister approached me afterwards and said he appreciated the quiet sense of hope in my message. Then we drove to Brattleboro, Vermont, where we had a mini-reunion with several walkers.

I talked with Eric Herminghausen, veteran of the United States Walk for the Earth. Eric left the walk group in Durango, Colorado, and walked alone across the country and met up with the group outside of Washington D.C. He now lives in Burke, Vermont. "The walk was passing through the country faster than I wanted so I wanted to get a better feel for an area as I was going through," he said. "It was an evolving philosophy I had. By the time I hit the Mississippi, however, I was studying my map and trying to figure out how I could reach the East Coast before the winter, so it turned into something worse than what I was trying to get away from. So that was revealing. It turned into sort of a marathon event--walking through the country instead of fully experiencing it.

"I have very vivid memories today of the country and people I met on my own. For instance, in walking through Kentucky I met a young boy and he invited me to come home and meet his family and I ended up camping in their yard for a few days. One thing I discovered was my loner tendencies--not feeling comfortable being with a group. It's still a challenge today, but I appreciate partially what I missed and that is walking with a group and the community. I feel today that the walk people are part of my family. So it's sort of a regret that I separated from the walk."

For the past 18 years he has been holding the same job as the caretaker for an historic estate and trying to live a simple life respecting the earth. He built a house in the woods using a passive solar design and has been trying to minimize his impact on the planet.

I talked with Eric Herminghausen, veteran of the United States Walk for the Earth. Eric left the walk group in Durango, Colorado, and walked alone across the country and met up with the group outside of Washington D.C. He now lives in Burke, Vermont. "The walk was passing through the country faster than I wanted so I wanted to get a better feel for an area as I was going through," he said. "It was an evolving philosophy I had. By the time I hit the Mississippi, however, I was studying my map and trying to figure out how I could reach the East Coast before the winter, so it turned into something worse than what I was trying to get away from. So that was revealing. It turned into sort of a marathon event--walking through the country instead of fully experiencing it.

"I have very vivid memories today of the country and people I met on my own. For instance, in walking through Kentucky I met a young boy and he invited me to come home and meet his family and I ended up camping in their yard for a few days. One thing I discovered was my loner tendencies--not feeling comfortable being with a group. It's still a challenge today, but I appreciate partially what I missed and that is walking with a group and the community. I feel today that the walk people are part of my family. So it's sort of a regret that I separated from the walk."

For the past 18 years he has been holding the same job as the caretaker for an historic estate and trying to live a simple life respecting the earth. He built a house in the woods using a passive solar design and has been trying to minimize his impact on the planet.

Monday, June 25, 2007

The Tour Continues!

Cyndi and I left Tallahassee June 18th to begin the East Coast book tour. Our first stop was Atlanta, where we stayed with friends Holly and Craig Loveland and their four children. Holly was once a summer camp student of mine and now she is a summer camp teacher as well as a wonderful mother. We connected with folks at the Phoenix and Dragon Bookstore in Atlanta and had a warm gathering at the Dunwoody Nature Center. Holly's brother Paul Ingram drove down from Dahlonega to join us. Paul was on a three-week walk with us through the Pacific Northwest in the late 1990s. He recalled a wonderful memory of when we met with a group of Native American runners on the Quinalt Reservation and they allowed us to run with them for a mile and to carry their feathered staff. The staff had more than a hundred feathers attached to it, given to the group from native groups they connected with.

After visiting with relatives in South Carolina, Cyndi and I drove to the Big Apple. We quickly learned why country people shouldn't drive in New York. It is a bit nerve wracking with aggressive taxi drivers dominating the roads. We parked at the Quest Bookshop in Manhatten, waited until our heart rates returned to normal, and didn't get in the car again until we left. We walked to the United Nations, Central Park and several other gardens and parks. There are some beautiful spots of nature in the city. We met some very friendly people and enjoyed the fact that New York is pedestrian friendly. I gave a talk at the lecture hall adjacent to the bookstore and we had an interesting discussion afterwards. Topics ranged from the little people to the colors associated with the four directions. Now it's on to Massachusetts and Vermont where we will connect with several walk friends.

After visiting with relatives in South Carolina, Cyndi and I drove to the Big Apple. We quickly learned why country people shouldn't drive in New York. It is a bit nerve wracking with aggressive taxi drivers dominating the roads. We parked at the Quest Bookshop in Manhatten, waited until our heart rates returned to normal, and didn't get in the car again until we left. We walked to the United Nations, Central Park and several other gardens and parks. There are some beautiful spots of nature in the city. We met some very friendly people and enjoyed the fact that New York is pedestrian friendly. I gave a talk at the lecture hall adjacent to the bookstore and we had an interesting discussion afterwards. Topics ranged from the little people to the colors associated with the four directions. Now it's on to Massachusetts and Vermont where we will connect with several walk friends.

Thursday, May 3, 2007

Susi Stahl Palmrose, trying to continue the walker way

From Port Townsend, I drove down to Portland to visit with Susi Stahl Palmrose, who was on the United States and European walks. She grew up on an intentional community in Virginia and attended a Quaker high school. She was eighteen years old during the first walk; she turned nineteen on the last day in Washington D.C.. Now, she has three children and a husband. "One time on the walk in the Midwest," she recalled, "I was walking in the rain and it was kind of chilly. On the outside it would look kind of miserable. I saw pity on people's faces when they glanced my way as they were whizzing by in their metal boxes. But I was very happy and very content. I felt there was nothing else I'd rather be doing, a very peaceful feeling. I was right with the world."

"I joined the walk right out of high school so it was my way of stepping out into the world on my own. Everything was sharp and bright and interesting and new. I remember walking in California, I wanted to capture every sight and tell my family about it. And the experience of just walking is a way of being very real, down to the basics and very simple. You're right there on the road or in the mountains and you got there on your own two feet; that was an internal thing for me. I felt like I was not only doing something for my own benefit, but also setting a good example and a good expression for the rest of the world.

"I know now that those experiences that I was having are important to me for the rest of my life because now when I just take a short walk any where, it's almost like I can just tap into my old walker self. So it's more meaningful for me to just take a little walk. The walk formed something of who I am. Now, in my life I like to bike a lot, so I've transferred some of that to the bike. It can become a tiny revolutionary act of sanity in an insane world because you're slowing things down to a pace that's more natural. I think that our pace of life is unnatural and hasn't given anybody a better lifestyle. I like some things about technology, but a lot of it has made our lives more stressful. Just because we have more machines doing our work doesn't necessarily make us happy or give us more time to relax."

After the walks, Susi began to raise a family. She went back to school when her youngest son was old enough to attend kindergarten. "I wanted to help people in some way," she said. "Nursing was a good fit once I learned the philosophy of nursing. I try to help people where they're at and I'm trying to be non-judgemental and compassionate, even when people have destroyed themselves by their own lifestyle choices such as drugs, drinking, smoking and obesity. Those can be the symptoms of the unhealthiness of the earth; the opposite of what the walk stood for. The medical world is almost enabling the unhealthy lifestyle to continue by allowing people to live half sick by simply prescribing medicine or doing medical procedures, but I'm in the medical world. That's the conflict that I'm trying to work out. The challenge is to be unconditionally loving while knowing that people are accountable for their choices. It's not up to me to give them their lessons. It's up to them and God. But I do encourage them to make healthy choices." Susi tries to set a healthy example by riding her bicycle to work.

In raising her children, Susi tries to set a good example. "Angela (oldest child) has said that I'm more peaceful and relaxed than anyone she knows, so I was glad that I'm that way and she sees that. I've raised my children to be concerned about other living things; I think any living thing is just as important as humans. It's all part of the natural balance of things. I've tried to teach my kids that, but it's up to them to decide for themselves and figure out their own ways."

Tomorrow, we plan to do some hiking and we're doing a program for friends in the evening in her living room. Some friends who do not have vehicles plan to take the light rail system to a station that is only a short distance from Susi's house.

"I joined the walk right out of high school so it was my way of stepping out into the world on my own. Everything was sharp and bright and interesting and new. I remember walking in California, I wanted to capture every sight and tell my family about it. And the experience of just walking is a way of being very real, down to the basics and very simple. You're right there on the road or in the mountains and you got there on your own two feet; that was an internal thing for me. I felt like I was not only doing something for my own benefit, but also setting a good example and a good expression for the rest of the world.

"I know now that those experiences that I was having are important to me for the rest of my life because now when I just take a short walk any where, it's almost like I can just tap into my old walker self. So it's more meaningful for me to just take a little walk. The walk formed something of who I am. Now, in my life I like to bike a lot, so I've transferred some of that to the bike. It can become a tiny revolutionary act of sanity in an insane world because you're slowing things down to a pace that's more natural. I think that our pace of life is unnatural and hasn't given anybody a better lifestyle. I like some things about technology, but a lot of it has made our lives more stressful. Just because we have more machines doing our work doesn't necessarily make us happy or give us more time to relax."

After the walks, Susi began to raise a family. She went back to school when her youngest son was old enough to attend kindergarten. "I wanted to help people in some way," she said. "Nursing was a good fit once I learned the philosophy of nursing. I try to help people where they're at and I'm trying to be non-judgemental and compassionate, even when people have destroyed themselves by their own lifestyle choices such as drugs, drinking, smoking and obesity. Those can be the symptoms of the unhealthiness of the earth; the opposite of what the walk stood for. The medical world is almost enabling the unhealthy lifestyle to continue by allowing people to live half sick by simply prescribing medicine or doing medical procedures, but I'm in the medical world. That's the conflict that I'm trying to work out. The challenge is to be unconditionally loving while knowing that people are accountable for their choices. It's not up to me to give them their lessons. It's up to them and God. But I do encourage them to make healthy choices." Susi tries to set a healthy example by riding her bicycle to work.

In raising her children, Susi tries to set a good example. "Angela (oldest child) has said that I'm more peaceful and relaxed than anyone she knows, so I was glad that I'm that way and she sees that. I've raised my children to be concerned about other living things; I think any living thing is just as important as humans. It's all part of the natural balance of things. I've tried to teach my kids that, but it's up to them to decide for themselves and figure out their own ways."

Tomorrow, we plan to do some hiking and we're doing a program for friends in the evening in her living room. Some friends who do not have vehicles plan to take the light rail system to a station that is only a short distance from Susi's house.

Other Walks

Jean, a neighbor of David and Casey Gluckman--my hosts in Port Townsend--came over yesterday evening with books and a video about the Great Peace March of 1986. She was a thru-walker in the nine-month trek from California to Washington D.C. Our discussion the night before had stimulated renewed interest and memories.

The Great Peace March began with a central organizing group, a large budget, and well over a thousand marchers. Overhead was extremely high, however, and logistics for taking care of that many marchers were a nightmare. The central organizing group went bust in less than three weeks, leaving the walkers stranded in the Mohave Desert. But the human spirit can be strong, and much to the surprise of the media and others, most of the walkers reorganized and persevered; they ultimately completed the walk with much fanfare in Washington. The video was well done and inspirational, and afterwards, Jean exclaimed, "It's time to do another walk!"

In that vein, in San Francisco I had learned of another cross country walk being planned. Native American activist Dennis Banks is spearheading the coast to coast trek to begin next spring on the 30-year anniversary of the Native Americans' "Longest Walk." This one will be called the Longest Walk II. The main message of the walk: all life is sacred. To learn more, log onto http://www.longestwalk.org/.

The Great Peace March began with a central organizing group, a large budget, and well over a thousand marchers. Overhead was extremely high, however, and logistics for taking care of that many marchers were a nightmare. The central organizing group went bust in less than three weeks, leaving the walkers stranded in the Mohave Desert. But the human spirit can be strong, and much to the surprise of the media and others, most of the walkers reorganized and persevered; they ultimately completed the walk with much fanfare in Washington. The video was well done and inspirational, and afterwards, Jean exclaimed, "It's time to do another walk!"

In that vein, in San Francisco I had learned of another cross country walk being planned. Native American activist Dennis Banks is spearheading the coast to coast trek to begin next spring on the 30-year anniversary of the Native Americans' "Longest Walk." This one will be called the Longest Walk II. The main message of the walk: all life is sacred. To learn more, log onto http://www.longestwalk.org/.

Wednesday, May 2, 2007

WaHeLut Indian School

I spoke to John's class at the WaHeLut Indian school on Monday. The school was named for a Nisqually warrior and medicine man who resisted white settlement and whose power is said to have flowed from thunder and lightning. John's nine fifth graders were friendly, lively and interested in the walks. Afterwards, the class took outside to their school sweat lodge along the Nisqually River. One girl said she had participated in a sweat ceremony the day before. Another student said he received his Indian name in a sweat ceremony. All of them had participated in a sweat ceremony at one time or another and they knew the main purposes of the ceremony--the purification of mind, body and spirit.

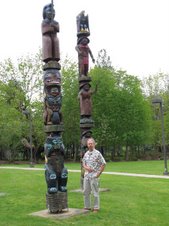

The school itself was immaculate, with totem poles adorning the front entrance and life-sized carvings of what was described as welcoming figures in the main entranceway. A large mural and dugout canoe depicted traditional life along the river. I met the principal and assistant principal and felt very welcome.

That evening, I joined John and his wife Susan in watching eight-year-old Keats Montrose play in a baseball game in the cold drizzle. I was convinced that the game would have been cancelled in normally drier climates. Just after Keats made a clutch hit with bases loaded, the game was stopped when the rain intensified and players were visibly shivering, along with spectators such as the one from Florida.

Now, I am staying with friends in Port Townsend, Washington. We had a neighborhood gathering last night, discussing the walks and other subjects. Overall, Port Townsend is an environmentally friendly community with a large group of people working to reduce their energy useage and "carbon footprint" in an effort to check the advance of global warming. Today, we hope to do some kayaking in Puget Sound.

The school itself was immaculate, with totem poles adorning the front entrance and life-sized carvings of what was described as welcoming figures in the main entranceway. A large mural and dugout canoe depicted traditional life along the river. I met the principal and assistant principal and felt very welcome.

That evening, I joined John and his wife Susan in watching eight-year-old Keats Montrose play in a baseball game in the cold drizzle. I was convinced that the game would have been cancelled in normally drier climates. Just after Keats made a clutch hit with bases loaded, the game was stopped when the rain intensified and players were visibly shivering, along with spectators such as the one from Florida.

Now, I am staying with friends in Port Townsend, Washington. We had a neighborhood gathering last night, discussing the walks and other subjects. Overall, Port Townsend is an environmentally friendly community with a large group of people working to reduce their energy useage and "carbon footprint" in an effort to check the advance of global warming. Today, we hope to do some kayaking in Puget Sound.

Sunday, April 29, 2007

Procession of the species

The Olympia "procession of the species" originated about 12 years ago to celebrate the natural world and to respond in a proactive way to attacks on the Endangered Species Act. Several hundred people--from school groups to white-haired elders--paraded through downtown Olympia yesterday, having donned elaborate costumes, masks, and pushing or pulling floats of polar bears, deep sea fish, a rhinosaurus and other animals. One life sized hammerhead shark was on wheels with a young girl sitting in the middle. There were also groups of humans portraying wolves, bees, flowers, black flies, salmon, raccoons, butterflies, various birds, peacocks, sasquatches, a unique rock man, and a host of other species and elements. A lively street dance completed the celebration.

The procession struck me as an attempt to restore tribalism and earth-oriented ceremonialism and celebration to western culture, filling a void that had largely been absent for centuries. And by the large participation in the parade and the thousands who watched, it was apparent that the procession was embraced by the community. Inspired by Olympia, other communities have been trying their own processions of the species. Doing the book program afterwards at Orca Books with a small but receptive audience seemed like a fitting end to an eventful day.

Today, we ventured to a coastal wildlife refuge and watched thousands of sandpipers, plovers, dunlins and other birds feed and move across exposed mud flats, seemingly like one organism. Many birdwatchers and photographers were clearly enjoying the spectacle, and so did we.

The procession struck me as an attempt to restore tribalism and earth-oriented ceremonialism and celebration to western culture, filling a void that had largely been absent for centuries. And by the large participation in the parade and the thousands who watched, it was apparent that the procession was embraced by the community. Inspired by Olympia, other communities have been trying their own processions of the species. Doing the book program afterwards at Orca Books with a small but receptive audience seemed like a fitting end to an eventful day.

Today, we ventured to a coastal wildlife refuge and watched thousands of sandpipers, plovers, dunlins and other birds feed and move across exposed mud flats, seemingly like one organism. Many birdwatchers and photographers were clearly enjoying the spectacle, and so did we.

Saturday, April 28, 2007

John Montrose, the man who won the horse

I am staying in Olympia with former walker John Montrose. Tonight, we are giving a program at Orca Books in downtown, but first I want to introduce you to John. John was a thru walker on the Walk for the Earth across the United States and on the Trail of Tears Walk. "I hadn't been aware of many of the Native American struggles, so visiting the reservations was a real eye opener. It formed a seed in my head of wanting to work with native peoples," he said. John is now in his eighteenth year as a teacher in Native American schools. John continued, "What really sticks with me from the walk was the feeling that any place could be my home. I looked forward to every day getting up and walking. It became sort of a meditative process. Winning the horse (on the Pine Ridge Reservation--chapter 12) was definitely a highlight. I love the idea of each person being able to pass on the idea of the quest for enlightenment. It was just a very powerful moment for me. I'm hoping we're all doing what we can to help each other on our journeys."

John is a teacher at the WaHeLut Indian School on the Nisqually River. He's been there 12 years, teaching fifth grade and middle school. Before that, he worked in a school on the Navajo Reservation. "It's funny, the kids assume that I am native. We've learned in their coastal language how to introduce ourselves and we state our tribe, and I say I'm from the Scotland Tribe, so they get a clue of my European ancestry. We work a lot on tolerance. That's one of my roles, helping to bridge the gap between the anglo culture and native traditional life. Our students have a difficult time mainstreaming into the western culture. Our goal is to help them both ways, to stress their cultural identity and to help them know their traditions, but we're caught in that dilemma of academic accountability, so it seems like our cultural activities and other core subjects are losing some ground to the standardized test regimen."

Some of the cultural traditions the young people are exposed to is the resurgence of the traditional canoe journeys. "We have a canoe curriculum we are trained in to introduce to the class--we have a language teacher at the school--so we learn canoe protocal and canoe songs and dances." The journeys last about two weeks. There is usually a host tribe and the group travels from Canada to the south Puget Sound areas, including stretches in the open ocean through the straights of Juan de Fuca. Some of that can be very challenging both physically and mentally. Some of the older students have done the journey. "It's a real visceral way to help them connect to their past and their ancestors," said John. At the end of each paddling day, the paddlers participate in a potlatch--food, song and dance, sometimes late into the night. As part of the school's summer school activity, a group of students helps with support work for the journey.

Some of the other cultural activities at the school are huckleberry picking, the first salmon ceremony, and an elders' dinner to honor local elders. Two traditional carvers are on the school staff that help students learn to carve a smaller scale canoe and paddles. One of the carvers also creates totem poles.

I plan to accompany John to his school on Monday to get a first-hand look, so I'll add some more later.

This afternoon, before the book program, we will observe the annual procession of the species through downtown Olympia, where participants don masks and elaborate costumes. The themes for the procession are earth, fire, air and water, so creatures from all four realms will be represented. Should be a fun time.

John is a teacher at the WaHeLut Indian School on the Nisqually River. He's been there 12 years, teaching fifth grade and middle school. Before that, he worked in a school on the Navajo Reservation. "It's funny, the kids assume that I am native. We've learned in their coastal language how to introduce ourselves and we state our tribe, and I say I'm from the Scotland Tribe, so they get a clue of my European ancestry. We work a lot on tolerance. That's one of my roles, helping to bridge the gap between the anglo culture and native traditional life. Our students have a difficult time mainstreaming into the western culture. Our goal is to help them both ways, to stress their cultural identity and to help them know their traditions, but we're caught in that dilemma of academic accountability, so it seems like our cultural activities and other core subjects are losing some ground to the standardized test regimen."

Some of the cultural traditions the young people are exposed to is the resurgence of the traditional canoe journeys. "We have a canoe curriculum we are trained in to introduce to the class--we have a language teacher at the school--so we learn canoe protocal and canoe songs and dances." The journeys last about two weeks. There is usually a host tribe and the group travels from Canada to the south Puget Sound areas, including stretches in the open ocean through the straights of Juan de Fuca. Some of that can be very challenging both physically and mentally. Some of the older students have done the journey. "It's a real visceral way to help them connect to their past and their ancestors," said John. At the end of each paddling day, the paddlers participate in a potlatch--food, song and dance, sometimes late into the night. As part of the school's summer school activity, a group of students helps with support work for the journey.

Some of the other cultural activities at the school are huckleberry picking, the first salmon ceremony, and an elders' dinner to honor local elders. Two traditional carvers are on the school staff that help students learn to carve a smaller scale canoe and paddles. One of the carvers also creates totem poles.

I plan to accompany John to his school on Monday to get a first-hand look, so I'll add some more later.

This afternoon, before the book program, we will observe the annual procession of the species through downtown Olympia, where participants don masks and elaborate costumes. The themes for the procession are earth, fire, air and water, so creatures from all four realms will be represented. Should be a fun time.

Friday, April 27, 2007

Pt. Reyes Station--Reconnecting, famous folk singer, russian royalty

What a day for connecting and reconnecting. Yesterday, Victoria, Randell and I drove to Pt. Reyes Station, just a few miles from the national park visitor's center where the Walk for the Earth began. Here, we reconnected with Jerry Lunsford, whom I hadn't seen for about 20 years. Jerry looked good, with long white hair, an energetic personality and a welcome sense of humor. During the 1984 walk, Jerry was an intern with the Mono Lake Committee, helping to fight for the lake's survival (covered in Chapter 9 of the book). My fondest memory of him was when, during the coldest day of walking, just before Mono Lake, he met the walkers with a gallon of hot chocolate in the back of his truck. He walked with our group several hundred miles to the Four Corners area of the Southwest. "I came away from the walk realizing that living by concensus was possible," he said.

Jerry is a strong force for community involvement at Pt. Reyes Station. He helped to establish a community radio station in 1999 and started his own radio program on Monday nights from 6:30-8:30--"The Hippie from Olema." It mostly plays bluegrass music, and he is developing a nationwide following through the Internet. Log in on KMR.org.

Jerry also helped to establish a community center, where he works as a technical director, helping to set up concerts, meetings, weddings and other events, among other duties. The center was built entirely by volunteer involvement and donations in 1989. "Building community is what it is all about for me," he said. His chat room on Monday nights helps him connect to people beyond Pt. Reyes. Jerry is also proud that Pt. Reyes Station is ground zero for organic food production in northern California, and Marin County was the first county to establish their own county organic certification program. Prince Charles visited a few years ago due to his interest in organics.

At a restaurant just before our book program at the local bookstore, Jerry introduced me to a silver-haired musician named Ramblin' Jack Elliott. "What intrument do you play?" I asked.

The man smiled. "Guitar," he said humbly.

"Do you mostly play around here?"

"Oh, I go to the East Coast, Europe and other places," he said quietly.

During his conversation with Jerry, I caught that Ramblin' Jack was playing with Willie Nelson and Emmy Lou Harris in May. Not shabby. Later, Jerry told me that Ramblin' Jack was a famous folk singer, a contemporary of Woodie Guthrie, who helped to inspire Bob Dylan in the 1950s. "Jack's been touring since the 1940s," said Jerry. The laugh was on me. My questions were like asking Bob Dylan what kind of songs he was known for.

Also in the restaurant was a member of the Russian royal family, Andrew Romanoff, the grand nephew of the last Russian czar. He was a painter and an acquaintance of Victoria, and she rushed over to see him. Having been born in England and having never setting foot in communist Russia, he had often conversed with Victoria before and after her 1987 Russian walk (see last blog). He was eventually able to visit Russia as part of an American painters' group, and later when the remains of his murdered ancestors were found and given a proper reburial. Fascinating story, but I didn't have a chance to chat with Andrew as we had to hurry to the bookstore for the program. It was a small but very engaged group and Jerry gave a great introduction to my powerpoint. All in all a very full day.

Today, I flew to Seattle to make my way down to Olympia for a program tomorrow night. During my next blog, I'll feature an interview with former walker John Montrose, who won a horse during a ceremony on the Pine Ridge Lakota Reservation (Chapter 12). Until then, peace.

Jerry is a strong force for community involvement at Pt. Reyes Station. He helped to establish a community radio station in 1999 and started his own radio program on Monday nights from 6:30-8:30--"The Hippie from Olema." It mostly plays bluegrass music, and he is developing a nationwide following through the Internet. Log in on KMR.org.

Jerry also helped to establish a community center, where he works as a technical director, helping to set up concerts, meetings, weddings and other events, among other duties. The center was built entirely by volunteer involvement and donations in 1989. "Building community is what it is all about for me," he said. His chat room on Monday nights helps him connect to people beyond Pt. Reyes. Jerry is also proud that Pt. Reyes Station is ground zero for organic food production in northern California, and Marin County was the first county to establish their own county organic certification program. Prince Charles visited a few years ago due to his interest in organics.

At a restaurant just before our book program at the local bookstore, Jerry introduced me to a silver-haired musician named Ramblin' Jack Elliott. "What intrument do you play?" I asked.

The man smiled. "Guitar," he said humbly.

"Do you mostly play around here?"

"Oh, I go to the East Coast, Europe and other places," he said quietly.

During his conversation with Jerry, I caught that Ramblin' Jack was playing with Willie Nelson and Emmy Lou Harris in May. Not shabby. Later, Jerry told me that Ramblin' Jack was a famous folk singer, a contemporary of Woodie Guthrie, who helped to inspire Bob Dylan in the 1950s. "Jack's been touring since the 1940s," said Jerry. The laugh was on me. My questions were like asking Bob Dylan what kind of songs he was known for.

Also in the restaurant was a member of the Russian royal family, Andrew Romanoff, the grand nephew of the last Russian czar. He was a painter and an acquaintance of Victoria, and she rushed over to see him. Having been born in England and having never setting foot in communist Russia, he had often conversed with Victoria before and after her 1987 Russian walk (see last blog). He was eventually able to visit Russia as part of an American painters' group, and later when the remains of his murdered ancestors were found and given a proper reburial. Fascinating story, but I didn't have a chance to chat with Andrew as we had to hurry to the bookstore for the program. It was a small but very engaged group and Jerry gave a great introduction to my powerpoint. All in all a very full day.

Today, I flew to Seattle to make my way down to Olympia for a program tomorrow night. During my next blog, I'll feature an interview with former walker John Montrose, who won a horse during a ceremony on the Pine Ridge Lakota Reservation (Chapter 12). Until then, peace.

Wednesday, April 25, 2007

The Tour Begins

My flight into San Francisco was supposed to arrive around noon, but with plane delays, I arrived only 7 hours late, just 45 minutes before I was supposed to speak at the Palo Alto Unitarian Church in the heart of Silicon Valley. After a friend picked me up, I walked in the door of the church just in time to set up and begin. It was a warm group of about 25 people, a few of whom were Native American. I met my friend and host Victoria Tregoning, who was on the Walk for the Earth. She mentioned later that setting up this event helped her make new connections, including one with a group doing traditional Native American sweat lodges in a backyard in downtown Palo Alto. "You would never have guessed in seeing this house from the front that there was a fire pit and a sweat lodge in the backyard," she said.

I did my powerpoint show of the Walk for the Earth in 1984 and of some current issues, such as global warming and steps we can take to reduce our carbon load. I gave hopeful examples of change that occurred since the walk such as the elimination of the Berlin Wall, the recovery of Mono Lake in California, and the restoration of an important river in Florida known as the Kissimmee. Then, we had a good discussion of what makes their area special and of some Native American issues. One man is helping to set up a reunion type of walk of the Native Americans' longest walk in 1979. That is set to occur early next year. Some in the audience are active in trying to free Native American prisoner Leonard Peltier, who many feel has been wrongly convicted of shooting an FBI agent during unrest in the early 1970s.

I am staying in the area for a couple of days with Victoria and her nephew Randall. Let me introduce Victoria. After the Walk for the Earth across the United States and Europe, Victoria got the walk bug and joined a group who walked from Leningrad (now St. Petersburg) to Moscow with 250 Americans and 250 Soviets from the different republics shortly after Gorbachov came into power in 1987. "It was so successful as a citizen diplomacy effort that a similar walk was done in 1988 with 250 Americans from all the different states and 250 Soviets from all the different republics across the United States," she said. "We did it in three segments and I was responsible for the food service in feeding 500 people a day for about two months with a mobile kitchen operation." Phew. And I thought we had a challenge feeding our group of 25 to 35 people on the Walk for the Earth.

Victoria took the food challenge because of her exposure to the Walk for the Earth and because she was a professional caterer. Still, she said it was mind blowing trying to obtain enough food to feed the walker army. "I learned a lot about the food distribution system in this country. And so many people came together to make it happen."

Since the walks, Victoria graduated from massage school and nursing school and now works as a massage therapist at a community center, mostly assisting elderly clients with their special needs. She also took under her wing a teenage nephew after her younger sister passed away. "The major thing that the walks affirmed to me is that they show that when people come together in a spirit of good will, amazing things are possible. But you have to trust that the goal will happen one step at a time. When enough people believe they can do something,they can do it."

While walking in Russia in 1987, she recalled how a bus load of East German young people pulled up to join. "They were talking about how the Berlin Wall would soon come down, but many in our group were skeptical, saying it would take a long time. But these teenagers, they were right. It was just a year and a half after that that it happened. That told me that the young people had their finger on the pulse, and we didn't quite believe it, even as open minded as we were."

One Soviet elder was overcome with emotion while carrying an American flag into Moscow, while Victoria carried the Soviet flag beside him. "His voice was quivering," Victoria recalled. "He kept saying, 'I can't believe I would ever see a day when I would be carrying an American flag into Moscow. It was one of those moments you described in your book, Doug, it is those moments that reaffirm your strength and your love for the planet amidst all the darkness. It's a core truth coming forth. It's like God, beyond words."

Thanks Victoria.

Today we are visiting the Native American art exhibit, "Living Traditions," at Stanford University, among other things.

I did my powerpoint show of the Walk for the Earth in 1984 and of some current issues, such as global warming and steps we can take to reduce our carbon load. I gave hopeful examples of change that occurred since the walk such as the elimination of the Berlin Wall, the recovery of Mono Lake in California, and the restoration of an important river in Florida known as the Kissimmee. Then, we had a good discussion of what makes their area special and of some Native American issues. One man is helping to set up a reunion type of walk of the Native Americans' longest walk in 1979. That is set to occur early next year. Some in the audience are active in trying to free Native American prisoner Leonard Peltier, who many feel has been wrongly convicted of shooting an FBI agent during unrest in the early 1970s.

I am staying in the area for a couple of days with Victoria and her nephew Randall. Let me introduce Victoria. After the Walk for the Earth across the United States and Europe, Victoria got the walk bug and joined a group who walked from Leningrad (now St. Petersburg) to Moscow with 250 Americans and 250 Soviets from the different republics shortly after Gorbachov came into power in 1987. "It was so successful as a citizen diplomacy effort that a similar walk was done in 1988 with 250 Americans from all the different states and 250 Soviets from all the different republics across the United States," she said. "We did it in three segments and I was responsible for the food service in feeding 500 people a day for about two months with a mobile kitchen operation." Phew. And I thought we had a challenge feeding our group of 25 to 35 people on the Walk for the Earth.

Victoria took the food challenge because of her exposure to the Walk for the Earth and because she was a professional caterer. Still, she said it was mind blowing trying to obtain enough food to feed the walker army. "I learned a lot about the food distribution system in this country. And so many people came together to make it happen."

Since the walks, Victoria graduated from massage school and nursing school and now works as a massage therapist at a community center, mostly assisting elderly clients with their special needs. She also took under her wing a teenage nephew after her younger sister passed away. "The major thing that the walks affirmed to me is that they show that when people come together in a spirit of good will, amazing things are possible. But you have to trust that the goal will happen one step at a time. When enough people believe they can do something,they can do it."

While walking in Russia in 1987, she recalled how a bus load of East German young people pulled up to join. "They were talking about how the Berlin Wall would soon come down, but many in our group were skeptical, saying it would take a long time. But these teenagers, they were right. It was just a year and a half after that that it happened. That told me that the young people had their finger on the pulse, and we didn't quite believe it, even as open minded as we were."

One Soviet elder was overcome with emotion while carrying an American flag into Moscow, while Victoria carried the Soviet flag beside him. "His voice was quivering," Victoria recalled. "He kept saying, 'I can't believe I would ever see a day when I would be carrying an American flag into Moscow. It was one of those moments you described in your book, Doug, it is those moments that reaffirm your strength and your love for the planet amidst all the darkness. It's a core truth coming forth. It's like God, beyond words."

Thanks Victoria.

Today we are visiting the Native American art exhibit, "Living Traditions," at Stanford University, among other things.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)