The Olympia "procession of the species" originated about 12 years ago to celebrate the natural world and to respond in a proactive way to attacks on the Endangered Species Act. Several hundred people--from school groups to white-haired elders--paraded through downtown Olympia yesterday, having donned elaborate costumes, masks, and pushing or pulling floats of polar bears, deep sea fish, a rhinosaurus and other animals. One life sized hammerhead shark was on wheels with a young girl sitting in the middle. There were also groups of humans portraying wolves, bees, flowers, black flies, salmon, raccoons, butterflies, various birds, peacocks, sasquatches, a unique rock man, and a host of other species and elements. A lively street dance completed the celebration.

The procession struck me as an attempt to restore tribalism and earth-oriented ceremonialism and celebration to western culture, filling a void that had largely been absent for centuries. And by the large participation in the parade and the thousands who watched, it was apparent that the procession was embraced by the community. Inspired by Olympia, other communities have been trying their own processions of the species. Doing the book program afterwards at Orca Books with a small but receptive audience seemed like a fitting end to an eventful day.

Today, we ventured to a coastal wildlife refuge and watched thousands of sandpipers, plovers, dunlins and other birds feed and move across exposed mud flats, seemingly like one organism. Many birdwatchers and photographers were clearly enjoying the spectacle, and so did we.

Sunday, April 29, 2007

Saturday, April 28, 2007

John Montrose, the man who won the horse

I am staying in Olympia with former walker John Montrose. Tonight, we are giving a program at Orca Books in downtown, but first I want to introduce you to John. John was a thru walker on the Walk for the Earth across the United States and on the Trail of Tears Walk. "I hadn't been aware of many of the Native American struggles, so visiting the reservations was a real eye opener. It formed a seed in my head of wanting to work with native peoples," he said. John is now in his eighteenth year as a teacher in Native American schools. John continued, "What really sticks with me from the walk was the feeling that any place could be my home. I looked forward to every day getting up and walking. It became sort of a meditative process. Winning the horse (on the Pine Ridge Reservation--chapter 12) was definitely a highlight. I love the idea of each person being able to pass on the idea of the quest for enlightenment. It was just a very powerful moment for me. I'm hoping we're all doing what we can to help each other on our journeys."

John is a teacher at the WaHeLut Indian School on the Nisqually River. He's been there 12 years, teaching fifth grade and middle school. Before that, he worked in a school on the Navajo Reservation. "It's funny, the kids assume that I am native. We've learned in their coastal language how to introduce ourselves and we state our tribe, and I say I'm from the Scotland Tribe, so they get a clue of my European ancestry. We work a lot on tolerance. That's one of my roles, helping to bridge the gap between the anglo culture and native traditional life. Our students have a difficult time mainstreaming into the western culture. Our goal is to help them both ways, to stress their cultural identity and to help them know their traditions, but we're caught in that dilemma of academic accountability, so it seems like our cultural activities and other core subjects are losing some ground to the standardized test regimen."

Some of the cultural traditions the young people are exposed to is the resurgence of the traditional canoe journeys. "We have a canoe curriculum we are trained in to introduce to the class--we have a language teacher at the school--so we learn canoe protocal and canoe songs and dances." The journeys last about two weeks. There is usually a host tribe and the group travels from Canada to the south Puget Sound areas, including stretches in the open ocean through the straights of Juan de Fuca. Some of that can be very challenging both physically and mentally. Some of the older students have done the journey. "It's a real visceral way to help them connect to their past and their ancestors," said John. At the end of each paddling day, the paddlers participate in a potlatch--food, song and dance, sometimes late into the night. As part of the school's summer school activity, a group of students helps with support work for the journey.

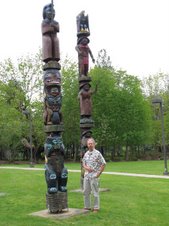

Some of the other cultural activities at the school are huckleberry picking, the first salmon ceremony, and an elders' dinner to honor local elders. Two traditional carvers are on the school staff that help students learn to carve a smaller scale canoe and paddles. One of the carvers also creates totem poles.

I plan to accompany John to his school on Monday to get a first-hand look, so I'll add some more later.

This afternoon, before the book program, we will observe the annual procession of the species through downtown Olympia, where participants don masks and elaborate costumes. The themes for the procession are earth, fire, air and water, so creatures from all four realms will be represented. Should be a fun time.

John is a teacher at the WaHeLut Indian School on the Nisqually River. He's been there 12 years, teaching fifth grade and middle school. Before that, he worked in a school on the Navajo Reservation. "It's funny, the kids assume that I am native. We've learned in their coastal language how to introduce ourselves and we state our tribe, and I say I'm from the Scotland Tribe, so they get a clue of my European ancestry. We work a lot on tolerance. That's one of my roles, helping to bridge the gap between the anglo culture and native traditional life. Our students have a difficult time mainstreaming into the western culture. Our goal is to help them both ways, to stress their cultural identity and to help them know their traditions, but we're caught in that dilemma of academic accountability, so it seems like our cultural activities and other core subjects are losing some ground to the standardized test regimen."

Some of the cultural traditions the young people are exposed to is the resurgence of the traditional canoe journeys. "We have a canoe curriculum we are trained in to introduce to the class--we have a language teacher at the school--so we learn canoe protocal and canoe songs and dances." The journeys last about two weeks. There is usually a host tribe and the group travels from Canada to the south Puget Sound areas, including stretches in the open ocean through the straights of Juan de Fuca. Some of that can be very challenging both physically and mentally. Some of the older students have done the journey. "It's a real visceral way to help them connect to their past and their ancestors," said John. At the end of each paddling day, the paddlers participate in a potlatch--food, song and dance, sometimes late into the night. As part of the school's summer school activity, a group of students helps with support work for the journey.

Some of the other cultural activities at the school are huckleberry picking, the first salmon ceremony, and an elders' dinner to honor local elders. Two traditional carvers are on the school staff that help students learn to carve a smaller scale canoe and paddles. One of the carvers also creates totem poles.

I plan to accompany John to his school on Monday to get a first-hand look, so I'll add some more later.

This afternoon, before the book program, we will observe the annual procession of the species through downtown Olympia, where participants don masks and elaborate costumes. The themes for the procession are earth, fire, air and water, so creatures from all four realms will be represented. Should be a fun time.

Friday, April 27, 2007

Pt. Reyes Station--Reconnecting, famous folk singer, russian royalty

What a day for connecting and reconnecting. Yesterday, Victoria, Randell and I drove to Pt. Reyes Station, just a few miles from the national park visitor's center where the Walk for the Earth began. Here, we reconnected with Jerry Lunsford, whom I hadn't seen for about 20 years. Jerry looked good, with long white hair, an energetic personality and a welcome sense of humor. During the 1984 walk, Jerry was an intern with the Mono Lake Committee, helping to fight for the lake's survival (covered in Chapter 9 of the book). My fondest memory of him was when, during the coldest day of walking, just before Mono Lake, he met the walkers with a gallon of hot chocolate in the back of his truck. He walked with our group several hundred miles to the Four Corners area of the Southwest. "I came away from the walk realizing that living by concensus was possible," he said.

Jerry is a strong force for community involvement at Pt. Reyes Station. He helped to establish a community radio station in 1999 and started his own radio program on Monday nights from 6:30-8:30--"The Hippie from Olema." It mostly plays bluegrass music, and he is developing a nationwide following through the Internet. Log in on KMR.org.

Jerry also helped to establish a community center, where he works as a technical director, helping to set up concerts, meetings, weddings and other events, among other duties. The center was built entirely by volunteer involvement and donations in 1989. "Building community is what it is all about for me," he said. His chat room on Monday nights helps him connect to people beyond Pt. Reyes. Jerry is also proud that Pt. Reyes Station is ground zero for organic food production in northern California, and Marin County was the first county to establish their own county organic certification program. Prince Charles visited a few years ago due to his interest in organics.

At a restaurant just before our book program at the local bookstore, Jerry introduced me to a silver-haired musician named Ramblin' Jack Elliott. "What intrument do you play?" I asked.

The man smiled. "Guitar," he said humbly.

"Do you mostly play around here?"

"Oh, I go to the East Coast, Europe and other places," he said quietly.

During his conversation with Jerry, I caught that Ramblin' Jack was playing with Willie Nelson and Emmy Lou Harris in May. Not shabby. Later, Jerry told me that Ramblin' Jack was a famous folk singer, a contemporary of Woodie Guthrie, who helped to inspire Bob Dylan in the 1950s. "Jack's been touring since the 1940s," said Jerry. The laugh was on me. My questions were like asking Bob Dylan what kind of songs he was known for.

Also in the restaurant was a member of the Russian royal family, Andrew Romanoff, the grand nephew of the last Russian czar. He was a painter and an acquaintance of Victoria, and she rushed over to see him. Having been born in England and having never setting foot in communist Russia, he had often conversed with Victoria before and after her 1987 Russian walk (see last blog). He was eventually able to visit Russia as part of an American painters' group, and later when the remains of his murdered ancestors were found and given a proper reburial. Fascinating story, but I didn't have a chance to chat with Andrew as we had to hurry to the bookstore for the program. It was a small but very engaged group and Jerry gave a great introduction to my powerpoint. All in all a very full day.

Today, I flew to Seattle to make my way down to Olympia for a program tomorrow night. During my next blog, I'll feature an interview with former walker John Montrose, who won a horse during a ceremony on the Pine Ridge Lakota Reservation (Chapter 12). Until then, peace.

Jerry is a strong force for community involvement at Pt. Reyes Station. He helped to establish a community radio station in 1999 and started his own radio program on Monday nights from 6:30-8:30--"The Hippie from Olema." It mostly plays bluegrass music, and he is developing a nationwide following through the Internet. Log in on KMR.org.

Jerry also helped to establish a community center, where he works as a technical director, helping to set up concerts, meetings, weddings and other events, among other duties. The center was built entirely by volunteer involvement and donations in 1989. "Building community is what it is all about for me," he said. His chat room on Monday nights helps him connect to people beyond Pt. Reyes. Jerry is also proud that Pt. Reyes Station is ground zero for organic food production in northern California, and Marin County was the first county to establish their own county organic certification program. Prince Charles visited a few years ago due to his interest in organics.

At a restaurant just before our book program at the local bookstore, Jerry introduced me to a silver-haired musician named Ramblin' Jack Elliott. "What intrument do you play?" I asked.

The man smiled. "Guitar," he said humbly.

"Do you mostly play around here?"

"Oh, I go to the East Coast, Europe and other places," he said quietly.

During his conversation with Jerry, I caught that Ramblin' Jack was playing with Willie Nelson and Emmy Lou Harris in May. Not shabby. Later, Jerry told me that Ramblin' Jack was a famous folk singer, a contemporary of Woodie Guthrie, who helped to inspire Bob Dylan in the 1950s. "Jack's been touring since the 1940s," said Jerry. The laugh was on me. My questions were like asking Bob Dylan what kind of songs he was known for.

Also in the restaurant was a member of the Russian royal family, Andrew Romanoff, the grand nephew of the last Russian czar. He was a painter and an acquaintance of Victoria, and she rushed over to see him. Having been born in England and having never setting foot in communist Russia, he had often conversed with Victoria before and after her 1987 Russian walk (see last blog). He was eventually able to visit Russia as part of an American painters' group, and later when the remains of his murdered ancestors were found and given a proper reburial. Fascinating story, but I didn't have a chance to chat with Andrew as we had to hurry to the bookstore for the program. It was a small but very engaged group and Jerry gave a great introduction to my powerpoint. All in all a very full day.

Today, I flew to Seattle to make my way down to Olympia for a program tomorrow night. During my next blog, I'll feature an interview with former walker John Montrose, who won a horse during a ceremony on the Pine Ridge Lakota Reservation (Chapter 12). Until then, peace.

Wednesday, April 25, 2007

The Tour Begins

My flight into San Francisco was supposed to arrive around noon, but with plane delays, I arrived only 7 hours late, just 45 minutes before I was supposed to speak at the Palo Alto Unitarian Church in the heart of Silicon Valley. After a friend picked me up, I walked in the door of the church just in time to set up and begin. It was a warm group of about 25 people, a few of whom were Native American. I met my friend and host Victoria Tregoning, who was on the Walk for the Earth. She mentioned later that setting up this event helped her make new connections, including one with a group doing traditional Native American sweat lodges in a backyard in downtown Palo Alto. "You would never have guessed in seeing this house from the front that there was a fire pit and a sweat lodge in the backyard," she said.

I did my powerpoint show of the Walk for the Earth in 1984 and of some current issues, such as global warming and steps we can take to reduce our carbon load. I gave hopeful examples of change that occurred since the walk such as the elimination of the Berlin Wall, the recovery of Mono Lake in California, and the restoration of an important river in Florida known as the Kissimmee. Then, we had a good discussion of what makes their area special and of some Native American issues. One man is helping to set up a reunion type of walk of the Native Americans' longest walk in 1979. That is set to occur early next year. Some in the audience are active in trying to free Native American prisoner Leonard Peltier, who many feel has been wrongly convicted of shooting an FBI agent during unrest in the early 1970s.

I am staying in the area for a couple of days with Victoria and her nephew Randall. Let me introduce Victoria. After the Walk for the Earth across the United States and Europe, Victoria got the walk bug and joined a group who walked from Leningrad (now St. Petersburg) to Moscow with 250 Americans and 250 Soviets from the different republics shortly after Gorbachov came into power in 1987. "It was so successful as a citizen diplomacy effort that a similar walk was done in 1988 with 250 Americans from all the different states and 250 Soviets from all the different republics across the United States," she said. "We did it in three segments and I was responsible for the food service in feeding 500 people a day for about two months with a mobile kitchen operation." Phew. And I thought we had a challenge feeding our group of 25 to 35 people on the Walk for the Earth.

Victoria took the food challenge because of her exposure to the Walk for the Earth and because she was a professional caterer. Still, she said it was mind blowing trying to obtain enough food to feed the walker army. "I learned a lot about the food distribution system in this country. And so many people came together to make it happen."

Since the walks, Victoria graduated from massage school and nursing school and now works as a massage therapist at a community center, mostly assisting elderly clients with their special needs. She also took under her wing a teenage nephew after her younger sister passed away. "The major thing that the walks affirmed to me is that they show that when people come together in a spirit of good will, amazing things are possible. But you have to trust that the goal will happen one step at a time. When enough people believe they can do something,they can do it."

While walking in Russia in 1987, she recalled how a bus load of East German young people pulled up to join. "They were talking about how the Berlin Wall would soon come down, but many in our group were skeptical, saying it would take a long time. But these teenagers, they were right. It was just a year and a half after that that it happened. That told me that the young people had their finger on the pulse, and we didn't quite believe it, even as open minded as we were."

One Soviet elder was overcome with emotion while carrying an American flag into Moscow, while Victoria carried the Soviet flag beside him. "His voice was quivering," Victoria recalled. "He kept saying, 'I can't believe I would ever see a day when I would be carrying an American flag into Moscow. It was one of those moments you described in your book, Doug, it is those moments that reaffirm your strength and your love for the planet amidst all the darkness. It's a core truth coming forth. It's like God, beyond words."

Thanks Victoria.

Today we are visiting the Native American art exhibit, "Living Traditions," at Stanford University, among other things.

I did my powerpoint show of the Walk for the Earth in 1984 and of some current issues, such as global warming and steps we can take to reduce our carbon load. I gave hopeful examples of change that occurred since the walk such as the elimination of the Berlin Wall, the recovery of Mono Lake in California, and the restoration of an important river in Florida known as the Kissimmee. Then, we had a good discussion of what makes their area special and of some Native American issues. One man is helping to set up a reunion type of walk of the Native Americans' longest walk in 1979. That is set to occur early next year. Some in the audience are active in trying to free Native American prisoner Leonard Peltier, who many feel has been wrongly convicted of shooting an FBI agent during unrest in the early 1970s.

I am staying in the area for a couple of days with Victoria and her nephew Randall. Let me introduce Victoria. After the Walk for the Earth across the United States and Europe, Victoria got the walk bug and joined a group who walked from Leningrad (now St. Petersburg) to Moscow with 250 Americans and 250 Soviets from the different republics shortly after Gorbachov came into power in 1987. "It was so successful as a citizen diplomacy effort that a similar walk was done in 1988 with 250 Americans from all the different states and 250 Soviets from all the different republics across the United States," she said. "We did it in three segments and I was responsible for the food service in feeding 500 people a day for about two months with a mobile kitchen operation." Phew. And I thought we had a challenge feeding our group of 25 to 35 people on the Walk for the Earth.

Victoria took the food challenge because of her exposure to the Walk for the Earth and because she was a professional caterer. Still, she said it was mind blowing trying to obtain enough food to feed the walker army. "I learned a lot about the food distribution system in this country. And so many people came together to make it happen."

Since the walks, Victoria graduated from massage school and nursing school and now works as a massage therapist at a community center, mostly assisting elderly clients with their special needs. She also took under her wing a teenage nephew after her younger sister passed away. "The major thing that the walks affirmed to me is that they show that when people come together in a spirit of good will, amazing things are possible. But you have to trust that the goal will happen one step at a time. When enough people believe they can do something,they can do it."

While walking in Russia in 1987, she recalled how a bus load of East German young people pulled up to join. "They were talking about how the Berlin Wall would soon come down, but many in our group were skeptical, saying it would take a long time. But these teenagers, they were right. It was just a year and a half after that that it happened. That told me that the young people had their finger on the pulse, and we didn't quite believe it, even as open minded as we were."

One Soviet elder was overcome with emotion while carrying an American flag into Moscow, while Victoria carried the Soviet flag beside him. "His voice was quivering," Victoria recalled. "He kept saying, 'I can't believe I would ever see a day when I would be carrying an American flag into Moscow. It was one of those moments you described in your book, Doug, it is those moments that reaffirm your strength and your love for the planet amidst all the darkness. It's a core truth coming forth. It's like God, beyond words."

Thanks Victoria.

Today we are visiting the Native American art exhibit, "Living Traditions," at Stanford University, among other things.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)